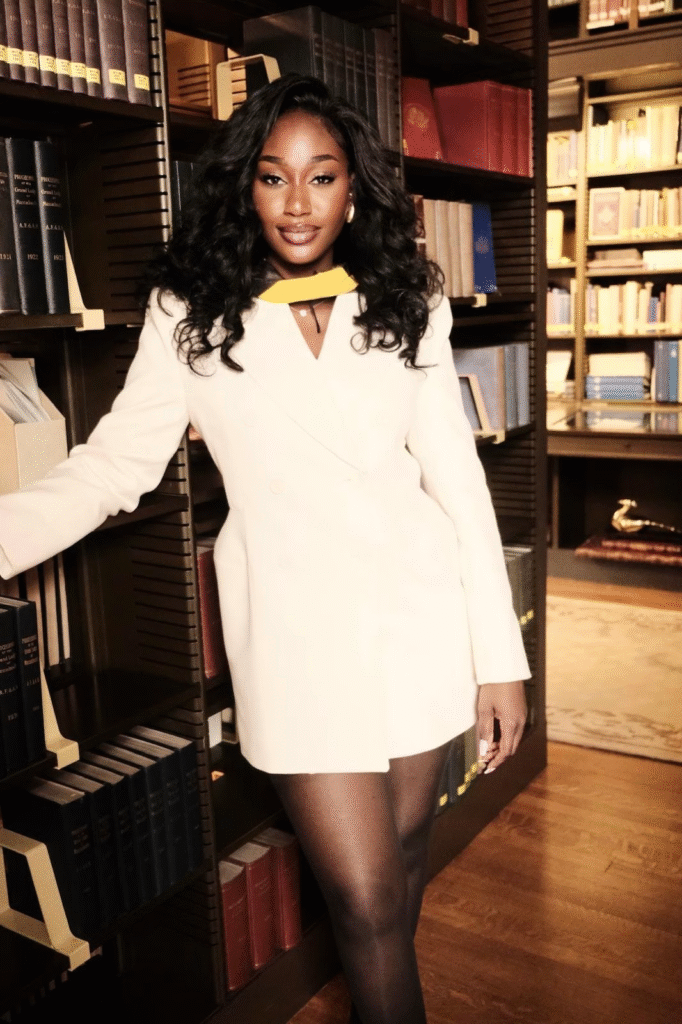

Content Syndication with Londondaily.news

A cohort that stepped into the world with purpose

A few months ago, Johns Hopkins University graduated a new healthcare cohort, and Isha Manneh walked across that stage with a point of view that is unusually clear for someone at the very start of a career. She does not talk about technology as an answer in search of a question. She talks about people, routines, and places, and about the quiet work of fitting good ideas to daily reality. Evidence only matters when it meets context, she tells me, and the purpose of any improvement is to make care feel clearer, kinder, and more dependable for the people who receive it and the people who deliver it. Long before graduation, she was already doing the unglamorous work that teaches this lesson in the bone. Screening days in borrowed rooms. Health talks in church halls. Helping families find their way through appointments and consent forms. That is where she learned that trust moves through ordinary channels, such as language, food, family, and faith, and that small changes, repeated faithfully, travel farther than grand launches that never fit the rhythm of a clinic.

What Hopkins added to raw experience

Hopkins’ layered method on top of instinct. The programme culture rewarded clear thinking and ethical discipline, but it also insisted that ideas be tested outside the classroom. Isha learned to read a care pathway the way you might read a map, not as a diagram on a slide but as a sequence of moments that feel different to reception, to a nurse, to a physician, and to a family. She learned to brief technical teams without losing the patient’s voice, and to translate population health evidence into steps a busy clinic can actually run. To keep herself honest, she set up a personal audit she calls Knowledge, Growth, and Application. Knowledge asks her to learn beyond the syllabus every week, Growth asks her to step outside comfortable settings every month, and Application asks her to point each quarter to a change that someone can feel. It is a modest routine, but it keeps vanity out of the work and it keeps outcomes in the centre of the frame.

How she thinks about improvement

Ask Isha what she looks for, and she will not give you slogans; she will give you scenes. A waiting room where families hear their names in a language they trust. A visit that starts on time because directions were clear and preparation made sense. A discharge that comes with explanations a grandmother can read without help. She cares about the order of small things because small things done in order turn into fewer missed visits, calmer conversations, safer handovers, and a staff that has a little more energy at the end of the day. She does not dismiss digital tools, but she measures them by human effects. If a tool cannot make the day smoother for patients and staff, it does not belong in the day.

When asked about two exciting healthcare systems

When asked about two exciting healthcare systems that she follows closely, Isha talks about the United States and the United Arab Emirates. She describes the United States as a place where complexity is the governing fact. There are many rules, many payers, and a workforce that is stretched, so any improvement that ignores pressure on time will fail to land. She describes the United Arab Emirates as a place where speed is the governing fact. Decisions move quickly, resources are real, ambition is visible, and the risk is to outpace preparation or to miss cultural nuance. The shared lesson, she says, is translation over export. A model that thrives in Boston will need different language, different consent flows, and different family roles to thrive in Abu Dhabi. Excellence travels when design honours the people in front of it. It stalls when the design assumes they are the same everywhere.

Where digital tools earn their place without the buzzwords

Isha is looking for work at the junction of care delivery and modern tools, but she speaks about technology in plain terms. She values simple automations that take friction out of appointments and referrals so people show up and feel ready. She values language support that sends reminders and instructions in the words patients use at home, not only the words they meet on a form. She values early outreach lists that help teams connect with people who are drifting away from care before problems harden. She is not interested in fashionable vocabulary. She is interested in results people can point to without a slide deck, like steadier follow-up, fewer gaps between visits, and a calmer pace inside clinics that are often doing the best they can with what they have.

What sets her apart in a hiring room

Many candidates sell a narrow specialism. Isha brings range with discipline. She can sit with analysts and still translate for nurses. She understands why leaders need reports and why front desks need a kinder script. She designs for time, trust, and transfer. Time comes first, because improvement that steals minutes will not last. Trust comes next, because messages that ignore language and belief will not be heard. Transfer follows, because a win that cannot move from one site to the next is not yet a win. She writes playbooks with the people who do the work, so progress keeps its shape when it travels. That habit makes her comfortable in clinical operations conversations, in product discussions, and in project plans, which is where adoption succeeds or fails.

A first-year brief that people can feel

Ask what success would look like in a first year with a team in the United States or in the United Arab Emirates, and the answer is specific. Ship three improvements that anyone can feel. Clearer appointment journeys so fewer people fall through the cracks. Better preparation for visits so conversations are calmer and more productive. Earlier outreach to those at highest risk so small problems stay small. Keep the reporting cadence simple and regular so leaders and frontline teams see the same truth at the same time. Use plain language. Keep measures visible. Keep dignity and efficiency in the same sentence. The point is not to sound innovative. The point is to help people and to prove it.

The line that runs through it all

This profile began with listening, and it ends there. Isha believes that listening is not a soft skill. It is the operating principle that lets evidence become care. Listening turns research into routines, and it lets modern tools play a useful human role rather than a decorative one. She is ready to bring that approach to a team in the United States or in the United Arab Emirates, and to keep proving that when you start with people, results have a way of travelling. There is nothing flashy about that promise, which is exactly why it stands up.

Profile

Isha Manneh is a Johns Hopkins graduate and a globally focused healthcare specialist. Her experience spans public health, specialty clinics, medtech, community programmes, and consulting. She has supported equity analytics and communications at a state health department, coordinated patient care in an orthopaedic and regenerative medicine practice in New Jersey, strengthened customer support and data integrity at neuromodulation company electroCore, cofounded a community health network that leads youth outreach, and delivered strategy projects through the JHU Carey Community Consulting Lab. Isha brings a community-first lens and a cross-cultural perspective, translating research into clear appointment pathways, better visit preparation, and earlier outreach for people at higher risk. Her interests include maternal and child health, chronic disease management, clinician wellbeing, health equity, and culturally competent communication. She is exploring roles and collaborations across the United States, the United Arab Emirates, and other global hubs where listening, cultural intelligence, and disciplined execution can deliver outcomes that patients and staff can feel.